When I was growing up, the rule of thumb was – there are two things you don’t talk about in social gatherings.

1. Religion

2. Politics

Why have we stigmatized politics?

Perhaps we don’t want to ruin the positive vibes, or hear uncle Larry’s rant about Trudeau. The reality I think is we don’t know where someone will take the conversation and that conceptually, we won’t be discussing the same subject. This is because there is a very important distinction between the ideal of politics and what we actually have in everyday politics.

Politics the ideal is the arena of how we govern ourselves as a community. It deals with the prevailing “issues” of our time and is aimed at discussing and debating those issues in the public domain then paving a path forward through public and institutional acceptance or rejection. Everyday politics is “which party you associate with” and how “our group” thinks we should run things.

The ideal is about coming to conclusions based on reason and healthy debate. The every day is about coming to conclusions based on social reference and conformity bias.

Here is a list of political issues in 2020, US-based. Some to think about before proceeding:

- Do you support the legalization of same-sex marriage?

- Should the federal government institute a mandatory buyback program for assault weapons?

- Do you support the death penalty?

- Should businesses be required to have women on their board of directors?

- Are you in favor of decriminalizing drug use?

- Should social media companies ban political advertising?

- Should immigrants be required to learn English?

- Should cities open drug “safe havens”?

- Should terminally ill patients be allowed to end their own life?

Taking a stance on any of these issues starts with an understanding of your deep-down fundamental beliefs.

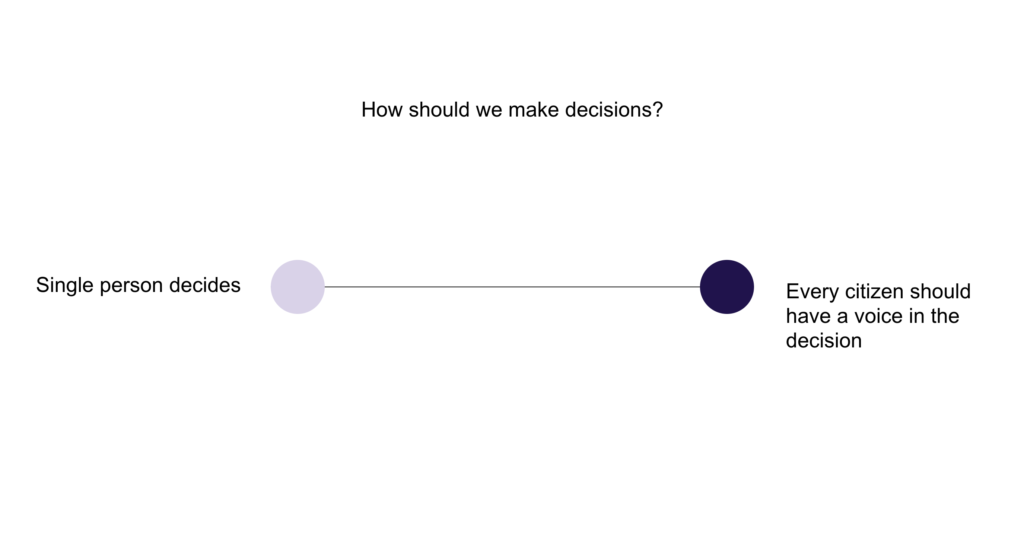

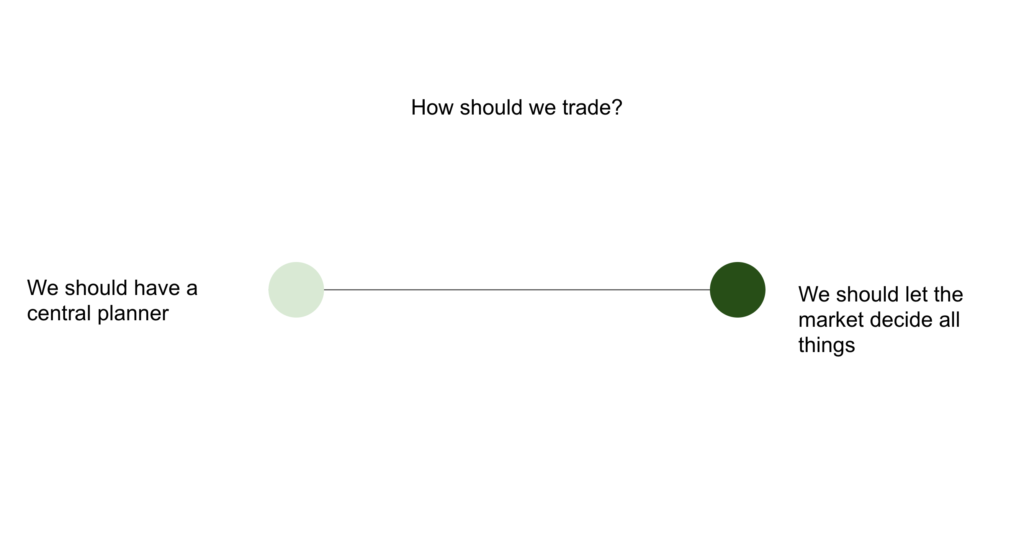

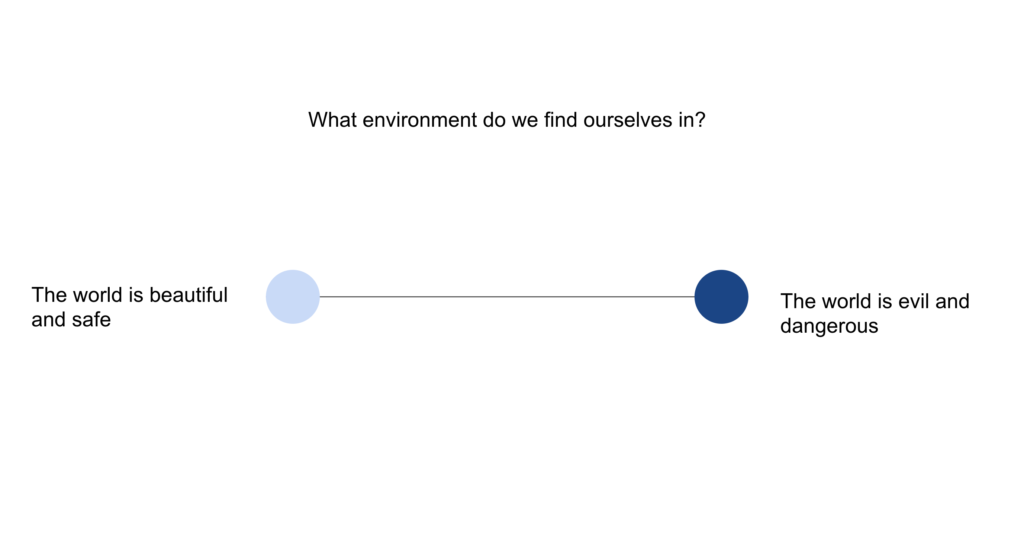

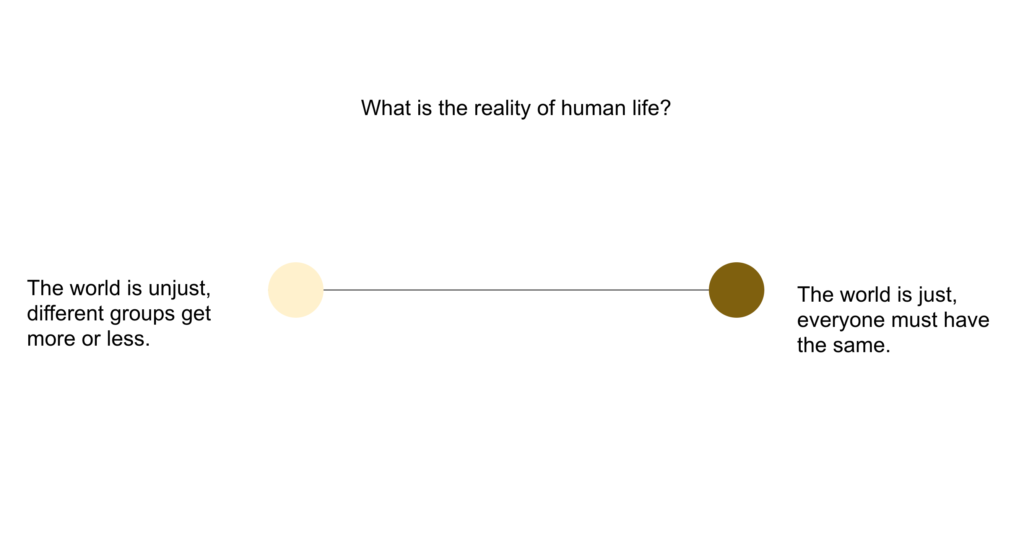

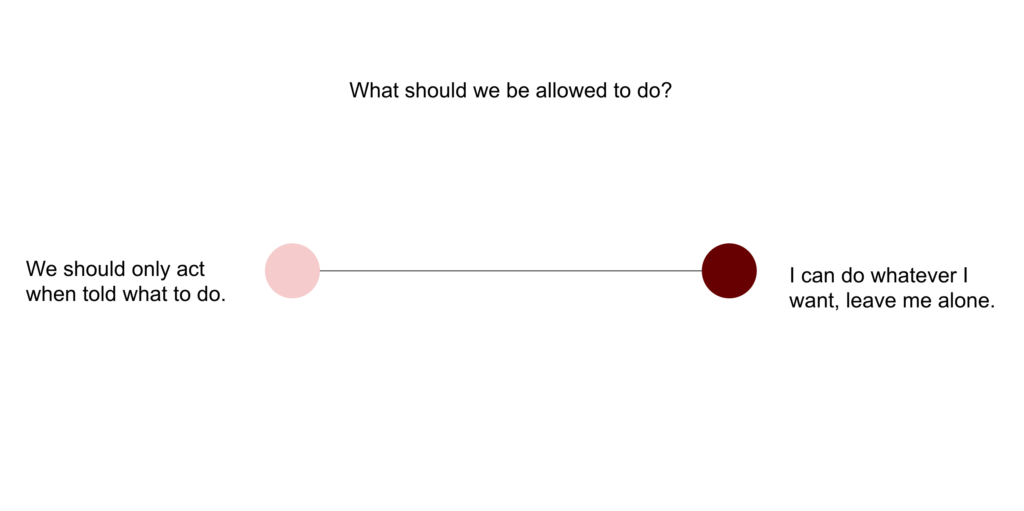

Fundamental Core Beliefs

Where we find ourselves on these spectrums will help us navigate the stance we should adopt on an issue based on what we truly believe, instead of what people like us think. Whenever we find ourselves questioning our stance based on the rhetoric of a good debater, we should cross-reference these core beliefs. When you are trying to find common ground with someone, reference these beliefs.

There are a lot more core beliefs I haven’t highlighted, but if you know of more please share them.

Personal Stance on Issues

Some issues are more important to individuals based on who they are, their background, and where they find themselves in life. As an example, if you’re older and wealthy, you’ll have a set of beliefs aligned to protecting what you have acquired. If you’re young and have little personal possessions your beliefs will be less protectionist. Our inclination can be driven by gender, region, race and ethnicity, family, religion…

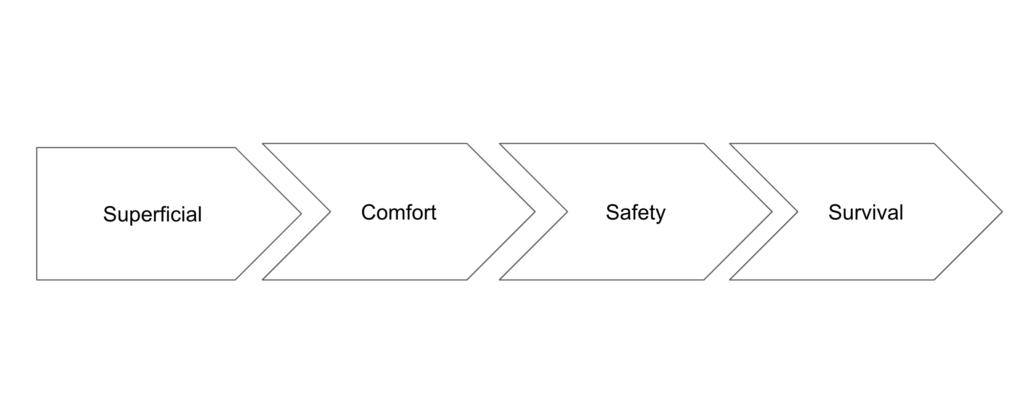

A good way of thinking about our relationship to issues is in stages.

Superficial: In this stage you’re unaffected by the issue, but you’re superficially aware of it, maybe a few members of your outer social circles are affected. You’re willing to speak about and take a stance, but you would abandon your stance under any pressure.

Comfort: In this stage you’re getting uncomfortable when people oppose you on this issue. Perhaps a close family member is affected by it, and your stance is backed by passion and deep empathy.

Safety: Your safety is under threat if this issue is not addressed. You could be hurt or worse if this issue is not society resolved in a way that aligns with your view.

Survival: If this issue is not adopted and accepted by society, your survival is at stake.

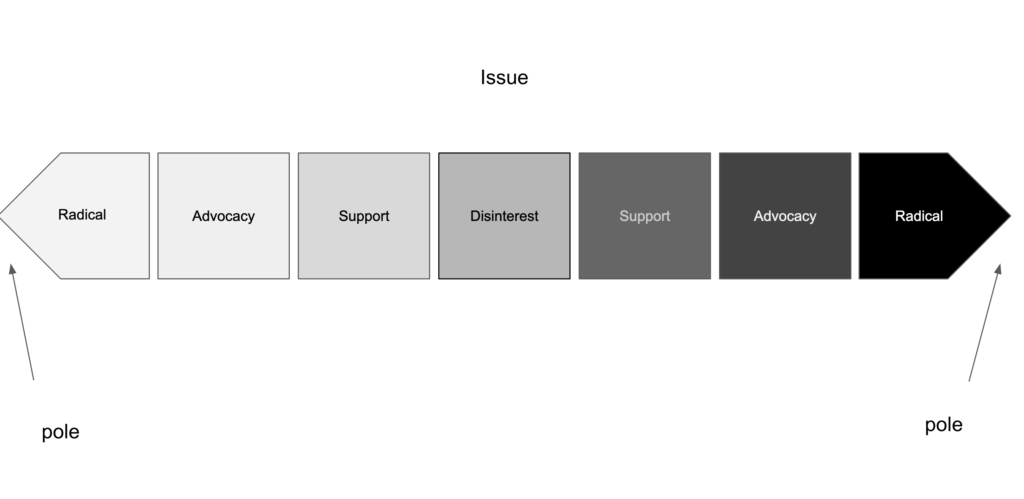

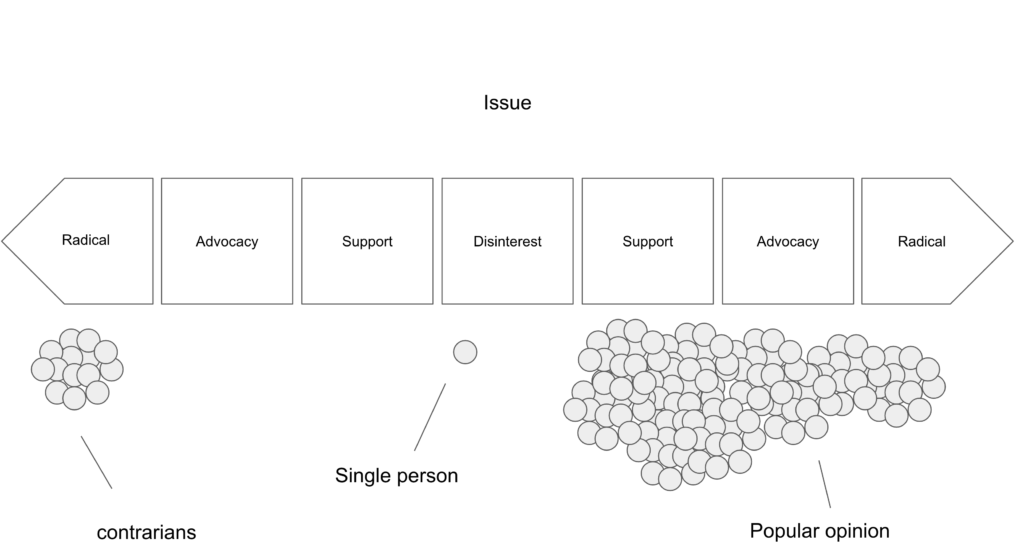

Spectrum of Stances on Issues

An individual’s relationship to an issue is a good starting point to understanding politics, but we need to zoom out and look at how different people can view the same issue in different ways.

Let’s take the issues of Euthanasia and abortion as examples. For many people, this may be a non issue since it doesn’t affect them. For others, it is an important topic worth taking a stance on. You have radicals on either side who will go as far as inflicting harm on others that are opposed to their view. Advocates with signs on street-corners trying to rally support for their views. Supportive types who donate and express their views at dinner parties.

If your personal comfort, safety, or survival is intimately tied to a pole of an issue, your tendency will be to that pole. To re-use euthanasia, if you or your family member is in chronic end of life pain, your stance may trend towards advocacy and radicalization on the issue.

Full stop here. At this point, we have underlying beliefs about how the world works and how we should govern ourselves as a society. We have individuals who have a personal stake on issues, and we have a spectrum of stances we can take on those issues. It would seem easy enough to resolve some of these issues at this point. If you aren’t personally affected by an issue, you shouldn’t have a stance. However, it is not that simple unfortunately.

Popular opinion and the movement of issues

The world is complicated, and there are a lot of issues that don’t personally affect us. Luckily, humans have a cognitive shortcut for making sense of complicated environments. We have a tendency to take cues for proper behavior in most contexts from the actions of others rather than exercise our own independent judgment.

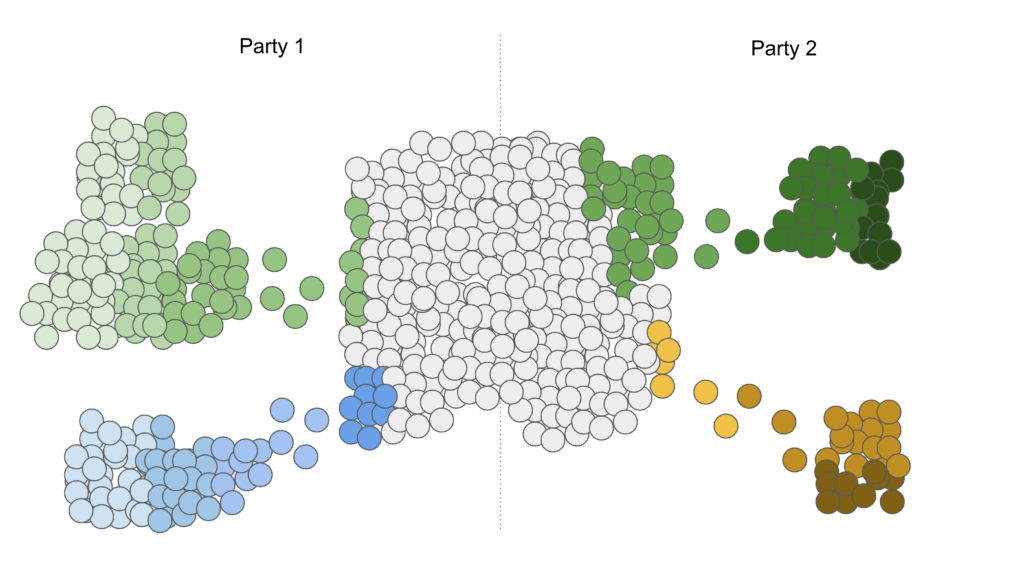

If a big enough group of people in and around our everyday life are adequately supportive, advocating or radicalized toward an issues pole, we’ll gravitate toward that stance.

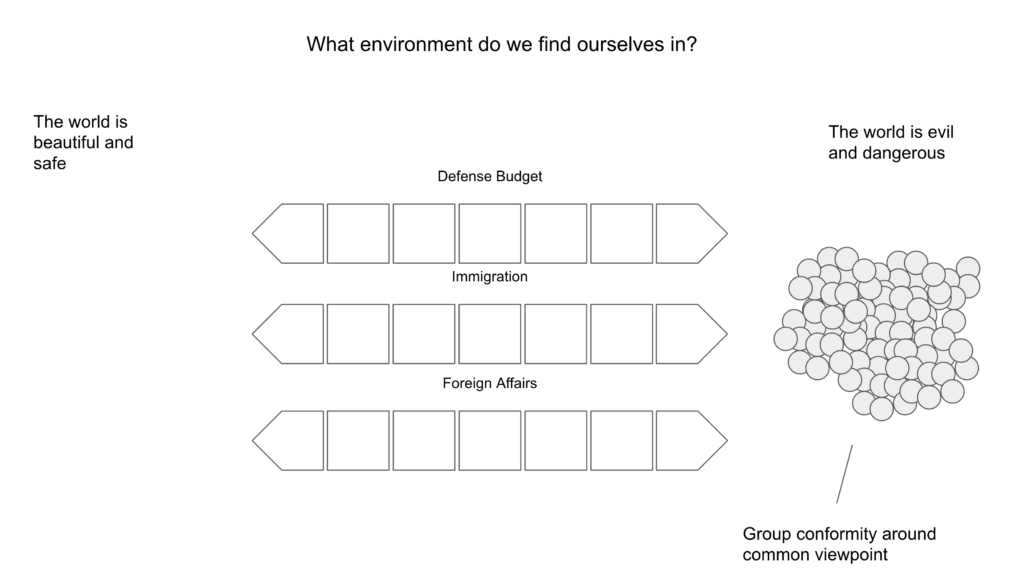

Not only that, but issues form natural groupings around fundamental beliefs, and popular opinion will start to re-shape your relationship to those beliefs.

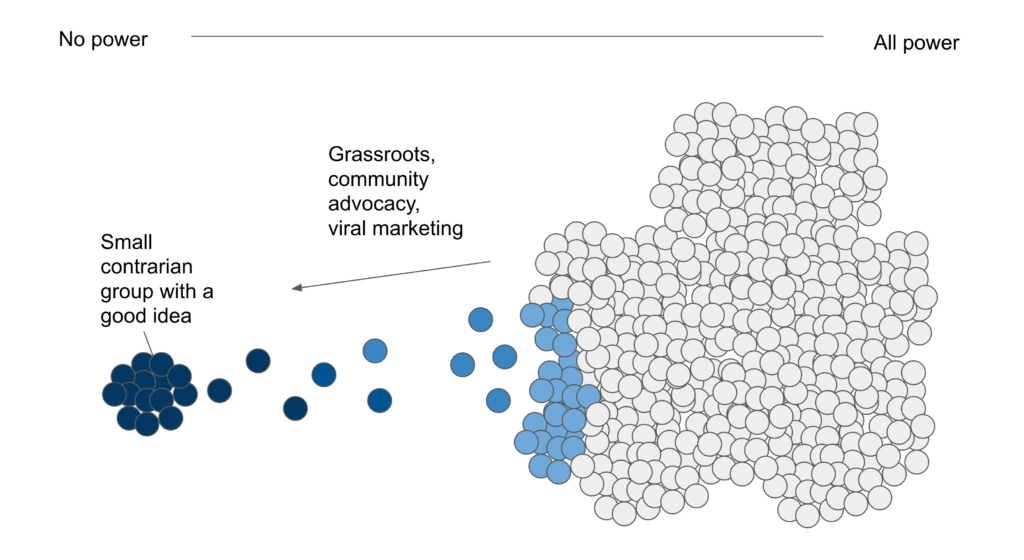

In some cases, taking cues from others is good, because popular opinion is right. In other cases, it can be very wrong. The right to same-sex marriage is a good example of an issue that popular opinion was against, until the early 2000s, when the tide shifted, and the popular opinion was for.

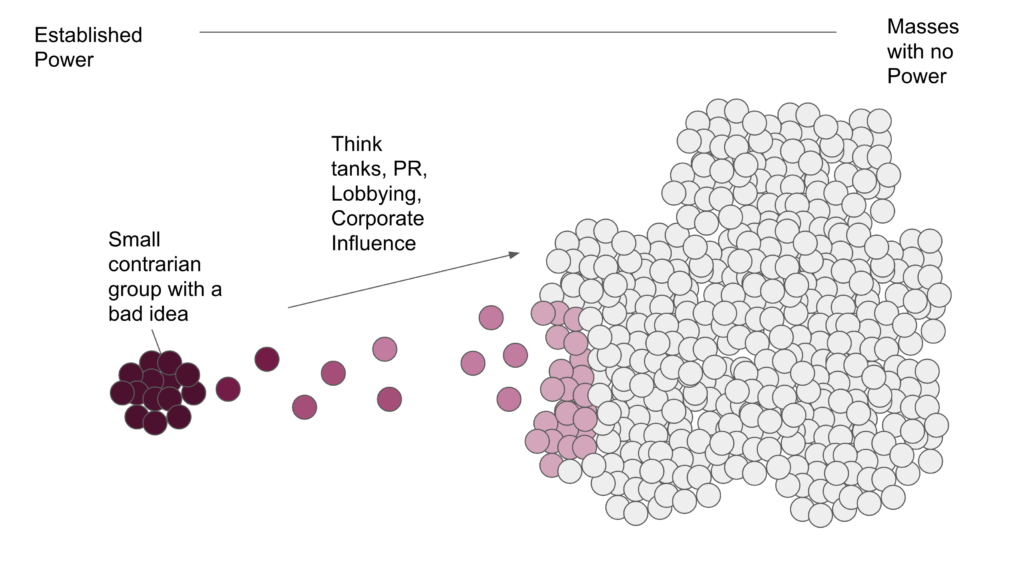

In other cases, like the historical case for tobacco. The masses are influenced by established power to take a stance on the issue that is contrary to their best interest.

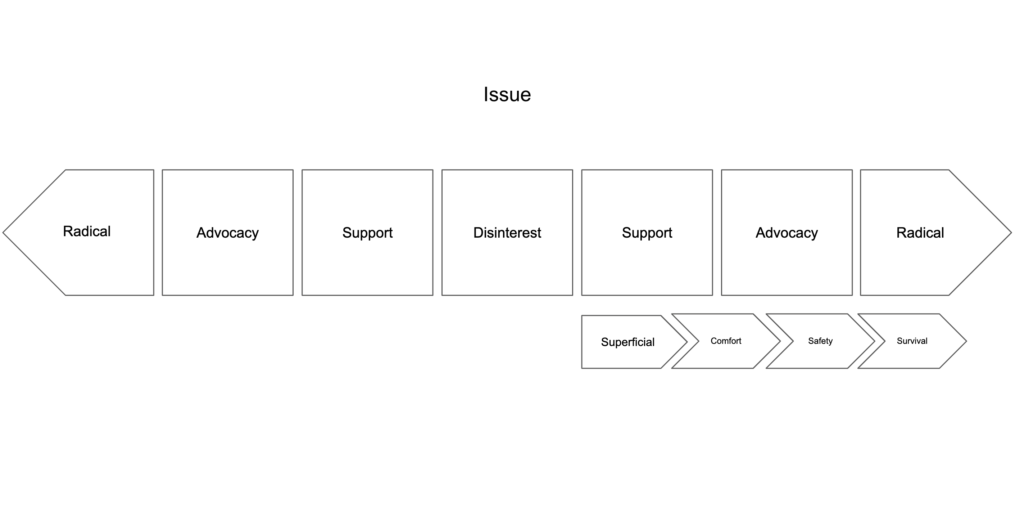

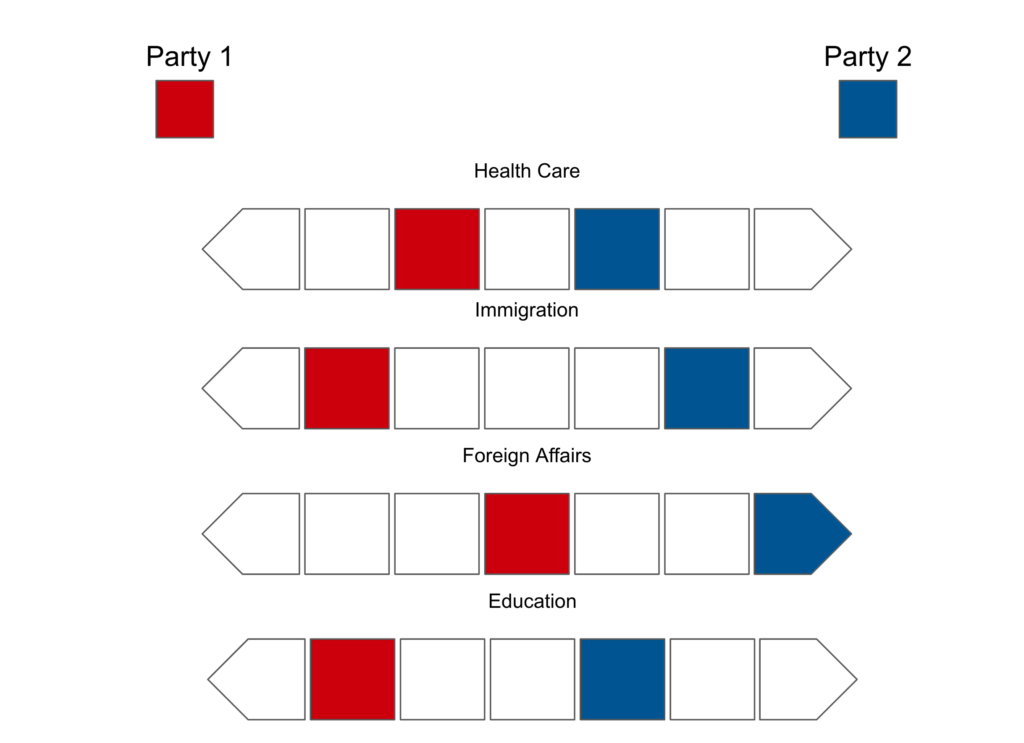

So we come to the game of political parties. Take stances of increasing and decreasing intensity on all timely issues in an effort to win the admiration of as many voters as possible to establish a period of monopoly on the governance of said people.

If we were to diagram this out using our issues spectrum with poles, it may look like this.

How to avoid being manipulated by this power game

Making good informed decisions as an individual contributor to our system of governance starts with understanding how to make your own decisions.

Inform yourself on the moving pieces of issues:

Who benefits? To what degree?

Who loses? To what degree?

What types of externalities will this issue create?

Will our collective lives be better?

Ignore rhetoric that blankets groups: When people in positions of power and influence use language that create’s an us vs them dynamic it’s to take advantage of your monkey brain. Ignore it.

Assume positive Intent: In order to have healthy dialogue on an issue and get to the heart of political discourse, you can’t assume the worst in someone. If you do, you’ll misinterpret their language and grid lock the conversation.

Bring the conversation back to the issue: Discuss the issue, not the party, or the person, or the group.

Open yourself up to the other person’s perspective by being an ally: Engage your empathy and be “on the person’s team” when collecting viewpoints, then digest what you’re hearing objectively and re-tell what you’re hearing before countering (if at all).

Find common ground in fundamental beliefs: In the end, pin pointing what core beliefs are motivating someone’s stance is the best path to understanding them. Find that common ground and work up from it toward the issue.

Happy Adulting!